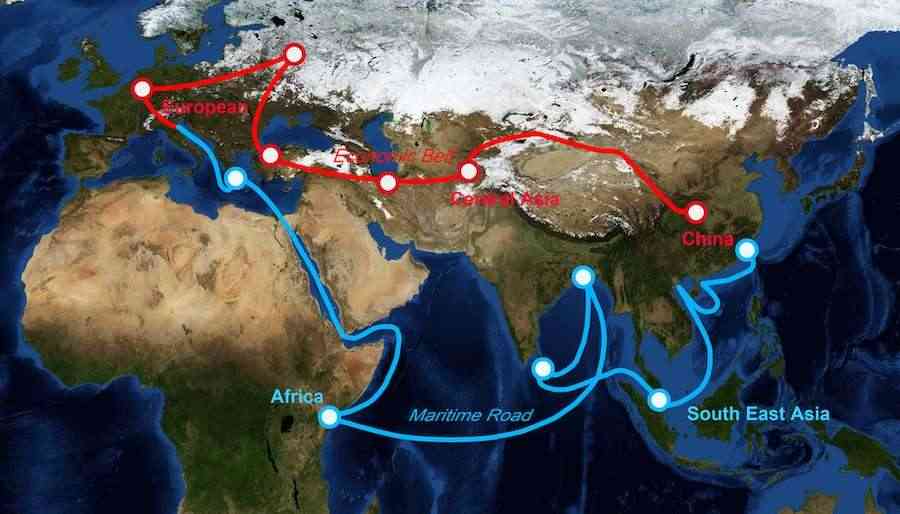

In an era marked by shifting geopolitical landscapes and economic realignments, Europe’s engagement with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) stands as a powerful case study in balancing ambition with caution. Launched in 2013, the BRI seeks to deepen global trade and economic integration through massive infrastructure investments. With trade routes extending across Asia, Africa, and into Europe, it aims to recreate and modernize the ancient Silk Road. Explore Europe’s evolving engagement with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) , balancing economic opportunities with strategic concerns.

Europe, with its world-class ports, transport corridors, and financial hubs, has naturally emerged as a critical node in this initiative. But while the infrastructure and investment promises are substantial, so are the political, economic, and strategic questions they raise.

Should Europe open its doors wider to Chinese capital in pursuit of prosperity? Or should it safeguard its autonomy by tightening investment screening and insisting on strict standards? The answer, it turns out, isn’t binary. Europe’s relationship with the BRI is shaped by a mosaic of national interests, EU-wide policies, and growing global rivalries.

In this blog, we’ll explore how European nations have responded to the BRI, what’s at stake for their economies and sovereignty, and what experts like Mattias Knutsson believe are the strategic imperatives for moving forward.

Europe’s Engagement with the China’s BRI: A Spectrum of Approaches

Southern Europe’s Embrace

Southern Europe, particularly countries like Greece, Portugal, and Italy, has welcomed Chinese investment as a way to recover from economic crises and improve logistics. Greece’s Piraeus Port is a flagship example. Acquired in stages by China’s COSCO Shipping, it has transformed into one of Europe’s busiest shipping hubs, significantly expanding its container capacity and operations.

Italy made headlines in 2019 by becoming the first G7 country to formally join the BRI. The move sparked concern among EU partners and the United States, but Italy argued that the agreement was commercial in nature, offering new opportunities for exports, tourism, and investment.

Yet by 2023, Italy was already reconsidering the agreement, signaling it may exit the BRI entirely. Critics within Italy cited limited economic return, diplomatic tension with allies, and strategic vulnerabilities.

Central and Eastern Europe’s Strategic Interests

The “17+1” framework — now effectively “China-Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) Cooperation” — included countries like Hungary, Serbia, and Poland, where Chinese infrastructure loans have funded rail upgrades, highways, and energy facilities. Serbia, a non-EU country, has welcomed billions in Chinese investment, including the Belgrade-Budapest railway modernization.

However, the initiative has lost steam. Lithuania exited the format entirely in 2021. Other nations have expressed disappointment with the slow pace of project delivery and growing dependency risks. EU officials have warned that bilateral agreements with China could fragment the Union’s common foreign policy.

Western Europe’s Guarded Openness

Germany, France, the Netherlands, and other Western European countries have not signed onto the BRI, but they have maintained strong economic ties with China. Germany, for instance, is China’s largest European trading partner, particularly in automobiles, chemicals, and machinery.

However, these nations have been cautious about infrastructure cooperation, especially in sensitive areas such as telecommunications (e.g., Huawei and 5G rollouts). National security, data sovereignty, and regulatory standards have been key sticking points.

Economic Opportunities and Strategic Concerns

Infrastructure and Trade Gains

The China’s BRI can improve Europe’s access to Asian markets, enhance connectivity through land and maritime corridors, and attract investment into neglected infrastructure sectors. For example:

- Over 10,000 freight trains ran between China and Europe in 2023, cutting shipping time to as low as 12 days.

- Chinese companies have participated in airport construction, industrial parks, and high-speed rail feasibility studies across the continent.

If implemented well, these projects could boost trade, reduce bottlenecks, and invigorate regional development.

Debt, Dependency, and Transparency

Concerns persist over financing terms. While wealthier EU nations generally self-fund infrastructure, smaller or crisis-hit economies have turned to external lenders. Critics point to opaque loan agreements, potential for political influence, and risk of foreign control over strategic assets.

Transparency is a major issue. The EU has urged recipient countries to fully disclose BRI-related contracts, assess long-term liabilities, and apply standard EU procurement rules.

Digital and Technological Risks

The Digital Silk Road, a part of the BRI, promotes Chinese-built data centers, 5G infrastructure, and e-commerce platforms in Europe. While these offer efficiency gains, there are concerns about data privacy, cybersecurity, and future-proofing digital sovereignty.

The EU’s Response to China’s BRI: Global Gateway and Beyond

In response to the China’s BRI, the European Commission launched the Global Gateway initiative in 2021 — a €300 billion plan to offer sustainable and transparent alternatives in areas like energy, digital infrastructure, transport, and education.

Global Gateway aims to:

- Promote EU values (transparency, democracy, rule of law)

- Counterbalance China’s growing influence

- Foster development partnerships with Africa, Asia, and Latin America

In parallel, the EU has tightened its foreign investment screening rules and built cross-border mechanisms to prevent risks to critical infrastructure, especially in energy and technology.

At the same time, Brussels continues to engage Beijing through summits, economic dialogues, and WTO channels, reflecting the EU’s interest in maintaining open trade while safeguarding sovereignty.

The Public View: Divided and Evolving

Surveys across Europe reveal mixed public attitudes:

- In countries like Hungary and Serbia, China is often viewed as a reliable partner.

- In Germany and France, skepticism is higher, with growing concern over authoritarian influence and job displacement.

Younger Europeans tend to support infrastructure development and sustainability but are cautious about China’s political model. Civil society, academia, and media play key roles in shaping perception and accountability.

Conclusion:

The Belt and Road Initiative has brought China and Europe closer together — economically, logistically, and politically. But it has also exposed fractures, both within the EU and in its relations with global powers.

Europe must now ask hard questions: Can it collaborate with China without compromising its values? How can it protect its strategic autonomy while embracing global connectivity? What role should democratic norms play in infrastructure diplomacy?

Mattias Knutsson, a leading voice in global procurement and strategic partnerships, offers a clear-eyed view:

“Europe has a unique opportunity to redefine how it engages with global infrastructure powers like China. It’s not about isolation or capitulation — it’s about setting the terms of partnership with clarity, fairness, and resilience.”

He advocates for:

- Stronger due diligence in cross-border contracts

- Alignment with long-term national interests

- Emphasis on transparency, local empowerment, and sustainability

According to Knutsson, “A strategic partnership is only valuable when both parties retain their integrity. Europe should lead by example — not just in policy, but in how it builds the future.”

His words reflect the core dilemma Europe faces: how to build bridges without becoming dependent — and how to lead with values in an era of complex cooperation.